How to Feel as Good as You Can, In Spite of Everything

This page offers a taste of Embodying Well-Being, also known as The Jiggle Good Book. The Table of Contents, Forward and Introduction, and some other parts are included below.

how to order new revised and extended version

Your body is organic, and you need to learn to listen to its rhythms until you feel that each cell is talking to you. When you develop such sensitive awareness of your body, you can tell it what to do. Your whole body feels light and blissful. It is liberating. You reach a point where your body and mind cooperate so perfectly that you feel body is mind and mind is body.

–Lama Yeshe

Table of Contents

Forward I

Forward II

Introduction

How to Use This Book

Why to Use This Book

How to Survive Doing Exercises

Why These Survival Hints

Basic Moves to Return to Well-Being

1. Yawning

2. Napping

3. Rocking

4. Jiggling

5. Sighing

6. Humming

7. Squatting

8. Stretching

9. Getting Up and Lying Down

10. Talking Funny

11. Patticake

12. Laughing

13. Skipping

14. Horse Lips

15. Playful Retching

16. Choo Choo Stomp

Moves From the Middle of the Road

17. Egg-laying Breath

18. Sipping Breath

19. Packing Breath

20. Slow Eye Rolls

21. Slow Head Rolls

22. Talking Tough

23. Setting Down the World

24. Turkey Flop

25. Grown-up Jiggling

26. Grown-up Humming

Advanced Moves to Well-Being

27. Grown-up Rocking (Alignment)

28. Stroking the Central Channel

29. Say AH

30. Heart Vase Breath

31. Mutuality

32. Presence Touching Presence

33. Resting the Heart Down

An Unusual Proposal

How to Continue

Why to Continue

Appendix A

Appendix B

From the Forward I

When the New York Times puts you on the front page, all the other newspapers and other media follow suit, and soon we were deluged with telephone calls and letters. Among them was one from Julie, who wrote us that she understood what we had found and knew other ways to produce the changes we had found. I invited her to come to our laboratory and show us. We attached the electrodes to different parts of her body to measure the changes in her physiology, and she easily followed our instructions about making the different facial movements. Just as we had found with our actors, she also generated the distinctive pattern of changes in her physiology for each different facial expression. Then she told us she could do it with her voice, and sure enough she did. And when she then both made the sounds and moved her face, we had to stop her, for the changes she produced were so large, they scared us. For example, we found an increase in heart rate of about ten beats per minute with most of our subjects. Julie generated an increase of over 100 beats per minute, and it happened instantly when she made a particular face and body. Equally astounding, she could generate these same changes without making a sound or moving a facial muscle, just by concentrating on her knowledge of how the body works.

A few years later, Julie gave a two-day workshop to a group of scientists studying emotion, in which she used an earlier version of the exercises described in this book. We were then her subjects, and we each experienced many of the changes she writes about.

She is a marvel. I don’t know if all of her explanations are correct, but the exercises do work, they can change your experience and sensations. I recommend them to you.

Paul Ekman, Ph.D.

Professor of Psychology

University of California Medical School, San Francisco

From the Forward II

Julie Henderson is one of the very few Westerners who have had training both in Buddhist forms of practice and in Western systems of body and energy work. Her book is an elegant synthesis of these traditions of healing.

Those who actually do the practices in this book will discover that “mindful” awareness always involves staying present with “bodily” sensations. This book shows us how to cultivate and sustain ever more subtle realms of sensation and presence. For example, the experience of joy is, for many, a somewhat rare occurrence. This book shows us how to jiggle into joy, and how to be with the love and compassion that may arise.

Written in a playful style, free from technical jargon, this work is destined to change the way we relate to our experience of embodiment.

Steven Goodman, Ph.D.

Core Faculty and Co-Director, Asian & Comparative Studies

Philosophy and Religion Department

California Institute of Integral Studies

San Francisco, California

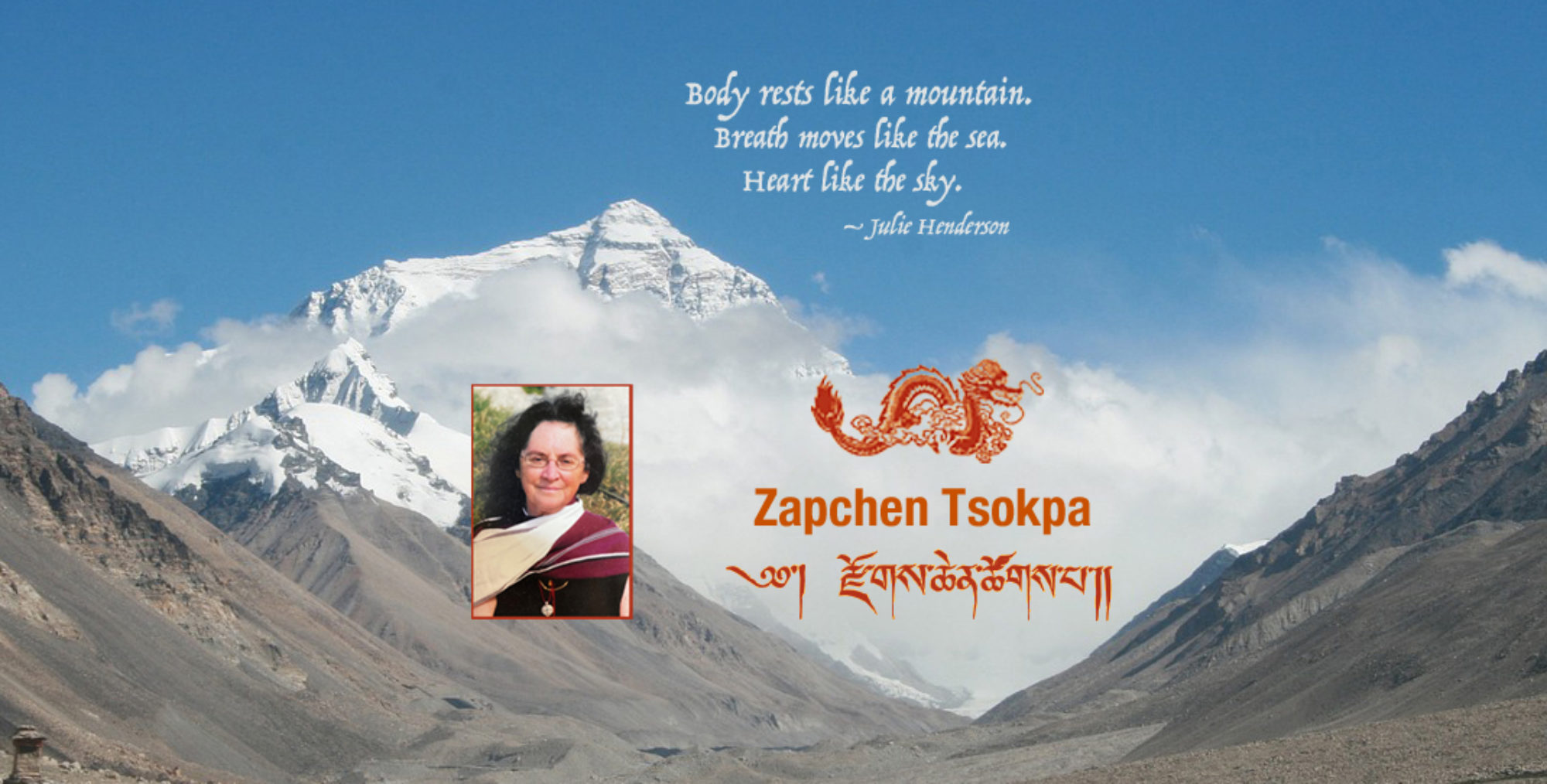

From the Introduction to Zapchen Somatics

Two things appeal to many people about our work: it moves directly towards pleasure and well-being, spending as little time as possible in negative states and repetitions of personal history; at the same time, it values the qualities of relationship that make the best sorts of psychotherapy attractive.

This way of working with human experience applies the same approaches to both inner self-regulation and outer intervention. We find that it applies not only to healing and therapy but to any field or practice human beings care to take up. It is pragmatic and experiential but not “accidental.” It gives real and immediate access to the possibility of well-being.

From the beginning, the student learns to recognize what can be done directly and immediately to increase freedom of movement, breath, and sound; to renew ground, alignment, and pulsation. At the same time, the student is given the congruent holding in relationship that supports well-being. Well-being itself promotes rapid maturation, including the occasionally unnerving sensations of being “someone else.” We support this radical level of change in the face of the fascinations of old habits of worry, pain, misery, depression, deprivation, and the other common challenges of the human condition.

Our approach is not pollyanna or pie-in-the-sky. It recognizes the tenacity of engrained habits and structures, but without dismay, and returns attention to what can be done now that does support the well-being that is immediately possible. We place the problems of history and conditioned reaction a definite second to action in the moment that renews well-being. That is to say, we move to free movement, breath, and sound, strengthen ground, restore alignment, and renew pulsation, then we consider what problem or dilemma may be felt to remain.

This book is an introduction to the simplest and most playful ways of restoring well-being. Many of the exercises are recognizable from childhood play. That is because this level of care for ourselves is inherent in how we function. They are simple, and they work.

Beyond these most basic and effective tools for being kind to ourselves, the book offers a glimpse towards some very high peaks of perception indeed. These more advanced methods benefit from good company in the learning and doing.

The word Zapchen comes from the Tibetan and has a very broad range of meanings, not all of them polite. From the order-rattling naughtiness of lively children to the unpredictable and spontaneously beneficial behavior of enlightened beings, Zapchen points to possibilities of change and maturation deeper than we can guess at. In a gesture that itself reveals the meaning, my heart teacher, Gyalsay Tulku Rinpoche, suggested Zapchen as the name for this work.

Welcome to the game.

Julie Henderson

Napa, California

March, 1999

Some circumstances will always be easier.

Vairocana Tulku, Rinpoche

Kathmandu, 1990

AN UNUSUAL PROPOSAL

When you feel bad or when you are facing a problem in your life, do some of these exercises BEFORE you “work on it.”

In particular: yawn, jiggle, do some egg-laying breaths. Describe your situation while Talking Funny. Move into the most easing alignment you can.Do more if you feel pleasurably drawn to do more.

Then notice:

– do you still feel bad?

– do you still have a problem?

– if you do, do you still feel it and regard it in the same way?

I know that this way of going about things – to move to feel good before you “fix” things –may seem bizarre, if not downright impossible, but I recommend it as a worthy experiment.

HOW TO CONTINUE

Doing a lot of these exercises won’t help. Doing a little bit, letting it go, resting, then doing a little more, WILL work.

If you will begin to let go of your habits of telling yourself you’re not getting it right, it’s too hard, you’re not doing enough, it’s not going to work anyway, and so on – and just do a bit of one exercise and, later, a bit more, then gradually the exercises and their effects will become “ordinary” for you. They will be as integrated and easy and effective as brushing your teeth.

This allowing the exercises and their effects to become an ordinary part of your experience-not requiring you to think about them in order to do them-we call embodiment. Technically, we are taking the doing out of the arena of cortical functioning and into the realms of the limbic system and hindbrain –so we don’t have to think about it anymore than we think about brushing our teeth. We just do it. In the same way that routinely brushing your teeth extends the life of your teeth, so doing even a few of these exercises in an ordinary way will gradually and persistently support your well-being in all circumstances.

WHY CONTINUE

Well, why not? To do these things is to offer yourself a true kindness. That kindness to yourself will influence how you are with everyone and in all circumstances.

APPENDIX A

Actually, it turns out there is a further “why” doing such exercises in this particular way is a good thing. That is, this procedure of doing a bit and resting, doing a bit and resting, and so on, turns out to be the process by which we stimulate the transference of what we learn into long term memory. The shift to long term memory is mediated by a protein molecule called CREB (cyclic AMP response element binding protein) and what provokes it to do its job is this very doing and resting and doing and resting that we have emphasized. The folks who do this sort of thing have demonstrated the workings of this protein with fruitflies and mice, and they are virtually certain it applies also to people and to all of us that learn(1).

Wonders never cease.

(1) Reported in Science News, vol. 146, no. 16, October 15, 1994, p. 244.